“There is more unknown than the unknown soldier - his wife 1- “

—

Slogan from the film Stand Up! A History of the Women’s Liberation Movement: 1970-1980, by Carole Rousopoulos

To my mother,

For her who made us all alone, my sister and me…

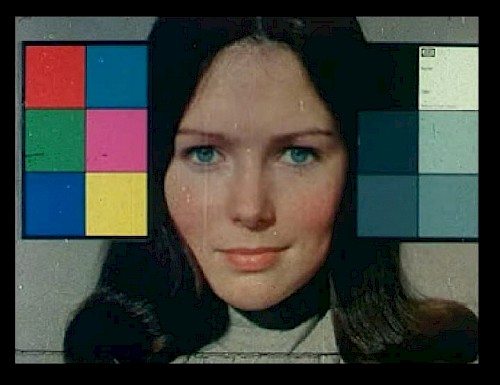

As if it was still necessary to prove that women directors not only existed without being nominees, but also that they had talent! A session was therefore necessary at the Kino Club to offer you a historical panorama and an explosive aesthetic anthology in order to establish the international richness of women’s and/or feminist cinema, whether in B movies, auteur films or experimental films! Excerpts from feature films and shorts will attempt to describe (as if it were possible…) certain recurring themes: the assumption of responsibility for one’s own desire (which has been obscured for too long), subversive and ironic sexual inversions (from the character to the cinematographic genre containing it), avant-garde political claims, made in favor of minorities, both ethnic and sexual, and marginalized people, as well as a particularly sensitive formal audacity that is often invited.

“Men will have to learn that, in the hierarchy of oppressions created by capitalism, their sexism and domination is another weapon in the hands of the ruling class to maintain itself. The exploited worker, faced with the even worse condition of his dependent wife, cannot be complacent about this - he must learn to see the source of the oppressive power that has degraded them both.” (Evelyn Reed, “Women: Caste, Class, or Oppressed Sex?”, 1971 article)

Woman, it is said, comes from man (deified and despotic to boot); from Adam’s rib, Zeus’ head, Pygmalion’s hands or Dr. Frankenstein’s, perhaps to better make us forget that it is the womb of woman that creates us, shapes us, polishes us, sculpts us and gives birth…

“I was making you a watery planet like my womb.” (Emma Santos, The Ill-Cast)

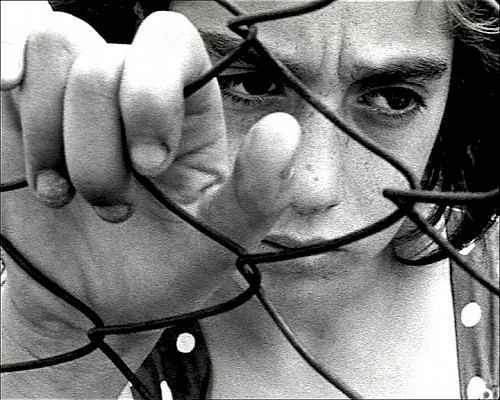

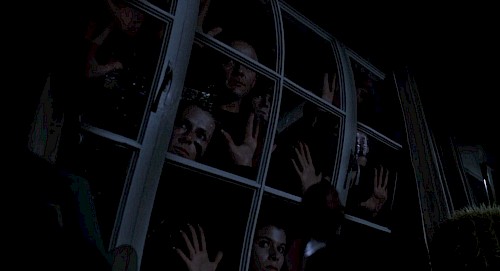

If women have (perhaps) a more heightened and nuanced sensitivity in what concerns physical and moral harassment, for example, it is undoubtedly because they are less vulnerable to the hegemonic male fantasy, very far, as for him, from any reality both psychological and emotional. Small inventory: the rape in Outrage (Ida Lupino, 1950), the massacre of a family in Sorority House Massacre (Carol Frank, 1986), the murderous self-defense in Blue Steel (Kathryn Bigelow, 1989), the marital rape in A Gun for Jennifer (Todd Morris and Deborah Twiss, 1997), the violent death of a brother in Bury Me Angel (Barbara Peeters, 1972) and Scarlet Diva (Asia Argento, 2000), the violent death of a child during the war in Travis (Kelly Reichardt, 2004), the daily violence of a father on his children in Girlfight (Karyn Kusama, 2000), the death of a father in the middle of the wilderness of the American pioneer West in The Frontier Experience (Barbara Loden, 1975)…

“Morality … The coward’s last bastion.” (Antonia Bird, Voracious)

American women directors also seem to do a better job of portraying the vulnerability of men. They free them from their stereotypical (and fantasized) manly straitjacket in favor of their secret wounds (Ralph Fiennes in Strange Days, Jason Holliday in Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason ), their self-sufficient gullibility (John Boles in Dorothy Arzner’s Craig’s Wife ), or their helplessness (Tim Daly in Janet Greek’s Spellbinder ). Often the men come out more concrete, closer to us (Edmond O’Brien in Ida Lupino’s The Bigamist and The Hitch-hiker , John Cassavetes and Peter Falk in Mikey and Nicky, and Charles Grodin in Elaine May’s The Heartbreak Kid )… And the beautiful vamps are finally not only hearts to be taken (or delivered), but the vain product of emasculated male fantasies that turn without mercy against their creator / oppressor consciously(The Velvet Vampire, Bury Me Angel, The Ladies Club, The Slumber Party Massacre, Blood Games, A Gun For Jennifer, Baise-moi) or not(Craig’s Wife).

Women seem (perhaps) more attuned to contemporary political issues or often more involved: the labor issue(V and V and Being Women by Cecilia Mangini), transgender and cross-dressing(The Secret of the Chevalier d’Éon by Jacqueline Audry, Let me die a woman by Doris Wishman, I don’t know by Penelope Spheeris, Appelez-moi Madame by Françoise Romand, Just one of the guys by Lisa Gottlieb…), Punk culture(Suburbia by Penelope Spheeris, Valley Girls by Martha Coolidge), the black American community(Black Panthers by Agnès Varda, I Am Somebody by Madeline Anderson, Attica by Cinda Firestone, More Dangerous than a Thousand Rioters by Kelly Gallagher), homosexuals(Portrait of Jason by Shirley Clarke), Vietnamese(Viet Flakes by Carolee Schneemann), those left behind and other marginal figures(Wanda by Barbara Loden, Smithereens by Susan Seidelman), prostitutes(Les prostituées de Lyon parlent by Carole Roussopoulos, Working Girls by Lizzie Borden), abortion(Y’a qu’à pas baiser by Carole Roussopoulos, Histoires d’A by Charles Belmont and Marielle Issartel)…

“Many women directors want to be directors in the end. Directors like others. As Maren Ade regrets, they hope that no one will notice that they are women… (…) Thinking about difference should not be confiscated by the conservative discourse (which replaces difference with hierarchy) nor by the gender discourse (which replaces difference with compartmentalization): thinking about difference is, on the contrary, the beginning of critical reflection.” (Editorial by Stéphane Delorme for Cahiers du cinéma n°681, September 2012).

These days, I’ve been told that we should even go through affirmative action… Before giving in to it completely, let’s look at the films that speak for themselves and by them and only them, let’s raise the exciting issue of women behind the camera and observe what they film differently (or not) from men…

—

Derek Woolfenden